The point of this post is to give a quick proof of a certain fact about bi-algebras. Namely, if is a graded bialgebra over a field

, with

, then

is a Hopf algebra.

This statement came up at the cluster algebras work shop in Oregon a few weeks ago, and most people seemed to feel it was mysterious. But, in fact, the concept of the proof is very simple. When your Hopf algebra is a group algebra, then the antipode is the map . One can write down the map

for positive

using just the bi-algebra structure; just take that formula and plug in

. Of course, the details are a little messier than that; hence this post.

I’ll give the necessary definitions below the fold, but this is written for people who are already happy with the definitions of bi-algebras and Hopf algebras.

A bi-algebra is a

-vector space with

-linear maps

,

,

and

such that

(1) Using as multiplication, and

as the multiplicative unit,

becomes an associative algebra.

(2) The dual of statement (1) holds for and

.

(3) is a map of algebras.

One major example of a bi-algebra is , where

is any semi-group (with a unit). Here

is the standard multiplication on

,

where

is the unit;

is

on the non-unit elements of

and

on

; and

for any

.

A bi-algebra is called a Hopf algebra if there is a -linear map

such that

. (These are all maps from

.) In the case of

, an antipode is precisely a map

such that

. I.e.

is a Hopf algebra if and only if the semigroup

has inverses i.e. if and only if

is a group. In general, an antipode should be thought of as a generalized inverse.

We’ll start out trying to build an antipode in an arbitrary bi-algebra. Of course, we’ll fail: Not all semi-groups are groups. But our failure will suggest a method that often succeeds.

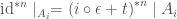

For any positive integer , define the map

from

by composing two maps: First, map

to

by using

over and over. Then map

by repeatedly using

. Because of the associativity and co-associativity axioms,

is well defined. If

is

, then

is the

-linear extension of the map

from

to itself. (Exercise!)

We would like to define the antipode to be ““. But what should this mean?

At this point, we introduce the hypothesis that will save us. Suppose that is graded, meaning that

, with

,

,

and

all maps of graded

-vector spaces. So, for example,

is contained in

. Suppose further that

.

In this case, must take

to

. Let’s see what this look like for

. First, we repeatedly use

to map

to

. In this direct sum, there are

-terms that look like

; there are

terms which look like

; there are another

which look like

; and there are

which are made of

‘s and

‘s. Since

is just our ground field, we can identify these tensor products with

,

,

and

respectively.

Using the co-unit axiom repeatedly, one shows that all of the different maps

which we get in this way are the same map. And similarly for the maps

,

and

.

Let’s call these maps ,

,

and

.

Going to is just the first half of computing

. The second half is mapping

back to

by repeated uses of

. As before, if we want to understand the terms that end up in

, we need to understand maps

, with

. And, as before, this comes down to just understanding 4 different maps:

, and similarly defined

,

and

.

Putting it all together,

This suggests an obvious definition for from

to

: just plug in

above to get

Here is the key fact:

For every

, the map

from

is a sum of a finite number (specifically

) of linear maps which are independent of

, with coefficients which are polynomials in

.

So we can define for any integer

. Now, when

and

, it is easy to see that

. This generalizes the equation

. Writing out a proof directly from the Hopf algebra axioms is a good exercise. For any

, the fact that

and

give the same map

is a polynomial identity. So it is also true for negative integers. In particular,

must be

, which is

. In other words,

is an antipode.

The same method of proof shows another, related result: Let be a bialgebra, and let

be the kernel of

. Set

, the

-adic completion of

. Then

is a Hopf algebra. Proof sketch: Show that

descends to a map

, and that, for each

, this map is a polynomial in

. Exercise: When

is commutative, what is the algebraic geometry meaning of this statement?

“We’ll start out trying to build an antipode in an arbitrary Hopf algebra”. Did you mean “arbitrary bi-algebra”?

Fixed, thanks.

At one of the problem sessions at the workshop, Alex Chirvasitu told me a generalization of the above result:

Theorem (probably Sweedler?): Let $C$ be a coalgebra and $A$ an algebra (both over a field $k$, for convenience; (co)unital and (co)associative, but not necessarily (co)commutative). Recall that $\operatorname{Hom}_k(C,A)$ of linear maps is a (noncommutative, unital) $k$-algebra with the convolution product. Recall also that the _coradical_ $C_0$ of $C$ is the direct sum of its simple subcoalgebras; it is a subcoalgebra of $C$. Given a linear map $f: C \to A$, let $f_0$ denote its restriction to $C_0$. Suppose that $f_0$ is invertible for the convolution product on $\operatorname{Hom}_k(C_0,A)$. Then $f$ is convolution-invertible.

This implies the above result because in a (nonnegatively) graded bialgebra, the coradical of the whole coalgebra is the coradical of its degree-$0$ part.

The proof is not much harder than what’s given above. The idea is that $C$ is the ind-limit of its coradical filtration, and you can invert $f$ as a power series.

But the underlying _reason_, I think, is interesting and geometric. The point is that coalgebras are a fairly basic form of “noncommutative spaces”. They do not allow for interesting topology, but any _set_ gives a coalgebra of linear combinations of the points in the set, and you can also easily add nilpotent “fuzz” to the points in the set, and stay in the world of cocommutative coalgebras.

Then the Theorem boils down to the following idea. The coradical of a coalgebra is essentially the “closed points” in a “noncommutative space”, and the structure theory of coalgebras assures that every coalgebra consists entirely of “infinitesimal neighborhoods of closed points”. A linear map $C \to A$ is something like an “$A$-valued function on $\operatorname{cospec}(C)$”. Then the Theorem just says that to tell whether a function is invertible in an infinitesimal neighborhood of a point, it’s enough to know that it’s invertible at the point, but it says this in the “noncommutative” world.

(Also, I’ve clearly been on MathOverflow too long — I just expect MathJax and Markdown to work everywhere. Apologies, then, for the TeX-heavy comment above; I think WordPress must require different conventions.)

Very instructive proof, even if the standard recursive construction is much easier. Here is a way to rewrite it in a way Hopf algebraists would immediately recognize the trick:

Consider the convolution algebra of all linear maps

of all linear maps  . The unity of this algebra is the map

. The unity of this algebra is the map  . Now, define a map

. Now, define a map  by

by  . Then,

. Then,  maps

maps  to

to  , and thus is “locally nilpotent”; more precisely, every

, and thus is “locally nilpotent”; more precisely, every  satisfies

satisfies  (where

(where  means “

means “ -th power in the convolution algebra”). Hence, for every fixed

-th power in the convolution algebra”). Hence, for every fixed  , the map

, the map  depends polynomially on

depends polynomially on  (because in any algebra, if

(because in any algebra, if  is a nilpotent element, then

is a nilpotent element, then  depends polynomially on

depends polynomially on  ). Since this map is exactly your

). Since this map is exactly your  , restricted to

, restricted to  , this explains your key fact.

, this explains your key fact.

By the way, a few flaws (I can’t stop pointing them out):

– There is an unprocessed LaTeX formula ($s : H \to H$) in the text.

– In the “key fact”, you probably don’t really mean to say $2^{n-1}$ – the number should be independent on $n$ for the proof to work. Here is, by the way, the explicit version of the key fact:

unless I am mistaken.

– I think you also have to require that $\epsilon$ is an algebra map in the definition of a bi-algebra.

Typos corrected. Thanks, darij! I thought that being a map of algebras follows from what I’ve already stated, but I could be wrong.

being a map of algebras follows from what I’ve already stated, but I could be wrong.